On Striking, Solidarity, and Jumpsuits

By E.R. Pulgar

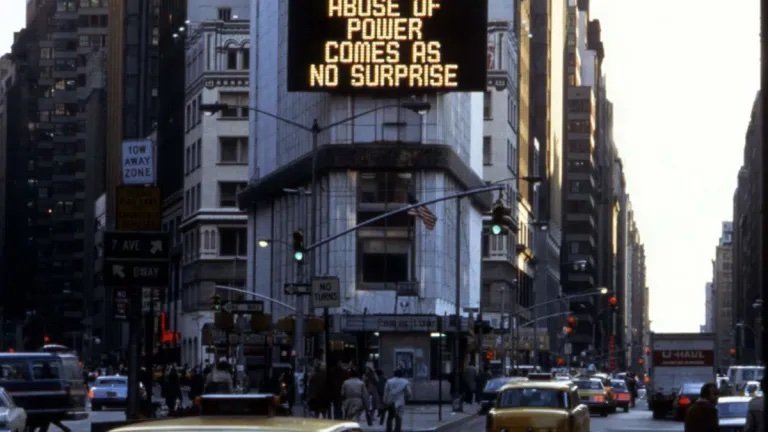

"Abuse of power comes as no surprise." Jenny Holzer's "Truisms" installation in NYC, 1980s. [Wikimedia Commons]

I wear a lot of jumpsuits. They’re warm, chic, easy—a complete outfit when you’re too depressed to think too hard about what to wear. For those saying it’s an adult onesie, you’re right and you should say it. My best friend — an Indigenous trans poet, social work student, lifelong activist and the most fashion-forward person I know — has had several discussions with me about how a blue-collar worker’s garb was appropriated as street fashion. On my end, the fit is bold, well-cut, and practical. It’s only ever a problem when you have to use the bathroom.

So, there I was, on the toilet at Butler Library, with my favorite black jumpsuit around my ankles, when the fire alarm rang. My literal worst nightmare came true. I finished my business, zipped back up, washed my hands with the loud trill in my ears, and headed out to a sea of students evacuating, fearing the worst.

I realized fairly quickly upon exiting the building that the alarm and our mass exodus was premeditated. The throng of students I was swept up in was greeted at the library steps by our peers decrying President Lee Bollinger’s salary on a megaphone, yelling about what the workers had been pushing to achieve for the week they had been on strike. It was November 10, one of the last real warm days in this strange post–global warming autumn. After listening for a bit, I ran to a nearby tent and connected to shoddy WiFi for my second Zoom class of the day, led by a professor who chose the virtual platform over the physical classroom so as to not cross the picket line.

On November 3, around three thousand unionized graduate and undergraduate teaching and research assistants kicked off what, as of November 16, became the largest ongoing strike in the United States. Brave members from the Student Workers of Columbia–UAW are striking for many of the same things workers both in and out of the university still have not gotten for years: a fair contract that includes liveable wages, dental and vision health insurance, better childcare support, and third-party arbitration for harassment cases. It sounds like a laundry list of things that we should have had a long time ago, particularly when the provider is an institution with a $14.35 billion endowment, an amount larger than the GDP of some countries.

We are now going on week five of a strike that has caused mixed emotions among students, and understandably so. After a year of class on Zoom with an IRL price tag, coming back to campus was a blessing (albeit with masks in place). As we began to get used to our strange new reality, we professors and students alike have had to readjust to stand in solidarity with the strike. Some professors opted for the virtual void, others coordinated off-campus, and all of it was kind of frustrating. The Writing Program has since made a statement that we return to the former in-person/remote-if-you-need-it model the university adopted post-pandemic.

Conversations with my colleagues, who I assumed might be on the same page as me, have been just as frustrating. Rather than solidarity with the strike, I’ve heard from a lot of my colleagues in the program (who themselves are not on the union or on strike) that they’re more upset about getting the short end of the stick, with their classes once again going remote or having class locations constantly shift because of the picket line. I get it, but let’s be clear: the aim of a strike is liberation. This cannot be brought about without an actual shaking up of the established order at Columbia that has left these workers no choice but to withhold their labor. That’s the point, and students who have had their schedules shifted around by a strike after having the program disrupted by COVID-19 have every right to be upset. If you’re reading this and you are upset, I urge you to look at the bigger picture.

This piece began in the form of a larger generalized statement by the Columbia Journal editors. The senior editors and I chose to frame it as an op-ed because 1) some of my colleagues were uncomfortable making a statement about the strike seeing as we’re non-union and not university-funded, and 2) I was, in fact, the only person on the Journal masthead actively withholding my labor in solidarity. My heart and thanks go to my colleagues at the Journal who have helped me shape this piece, and those who supported me over Slack and email on the statement we never made.

I can’t speak for my colleagues, but I personally felt uncomfortable continuing to work when we hadn’t made a statement. As someone who couldn’t attend this university without the scholarship I received; who is privileged every day to enjoy the bounty of resources here; who is living off late freelance writing checks, a loan, and work-study money; who knows what it’s like to be silenced in a room as a queer visibly non-white Latinx—it was no question to publicly support the strike. I won’t pretend that withholding my labor actually disrupted the Journal in any way (all my poetry colleagues here are efficient and have respected my decision), but I am writing this, so I can feel better about going back to my tiny contribution of making the online portion of this Journal more diverse, even as the strike rages on. If you’re a poet who’s been waiting to hear from me, this is why I’ve ghosted you—expect a reply ASAP.

The student workers on strike are the lifeblood that moves this university. What they are asking for is nothing less than the tools to function at their very best, with the dignity that they deserve—not as laborers but as human beings. To quote the statement made by the Writing Program’s full-time faculty via email near the beginning of the strike, our students who teach deserve to have their work recognized through contracts that strengthen our collective future. The administration of the University should provide guarantees that help union members realize this future.

This is a historic moment, an intense moment, a disruptive moment, and a key moment in the wider labor movement. What constitutes crossing the picket line has become blurry in these virtual-hybrid times. Taking a stand can feel incredibly lonely. It’s in these moments we must take refuge in our community and organize collectively in new ways. With the union entering mediation on their terms right before the holiday break, I can’t help but reflect on the things I have witnessed, experienced, and offered of myself in this time that gave me hope. A workshop colleague—always generous with their space for gatherings—hosted our class on one of the floors of their home, welcoming us with bagels and orange juice. I heard of other classes held in homes where students and professors drank wine and shared stories late into the night. I offered to hold a class in my living room, my Cancer rising self buzzing at the thought of making arepas with cheese and coffee for colleagues I’ve had the pleasure of creating and critiquing with since September.

It’s easy to forget, inside the formality of it all, that a lot of the best poetry comes not from the ivory tower but from the street. Columbia alum Allen Ginsberg got his real poetry education in the Lower East Side scene, in the mouths of boys at bars and in the raving moonlight of the fire escapes of this city. He wrote about the queer disposessed, and he got flak for it. I have always tried to prioritize listening to those who, in the words of the late Representative John Lewis, “make good trouble.” If that comes at the cost of my comfort as the diamond of the greater world is crushed out of the coal of this one, so be it. Zip up your jumpsuits. Yell, and yell loudly. Hold one another. Listen to each other.

At least on my end, it’s solidarity with the workers, now and always.

“It is our duty to fight for our freedom.

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and support each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains.”

—Assata Shakur, from Assata: An Autobiography

Donate to the Hardship Fund for Columbia Student Workers here.

About the author:

E.R. Pulgar is a Venezuelan American poet, translator, and critic based in Harlem. Their criticism has appeared in i-D, Rolling Stone, Playboy, and elsewhere. Their poems have appeared in PANK Magazine and b l u s h. They are an MFA candidate in poetry and literary translation at Columbia University, and serve as the Online Poetry Editor of the Columbia Journal. Born in Caracas and raised in Miami, they live in New York City.