Through the Eyes of Winged Things: The Birds and Ghosts of Jess Richards

By Melody Nixon

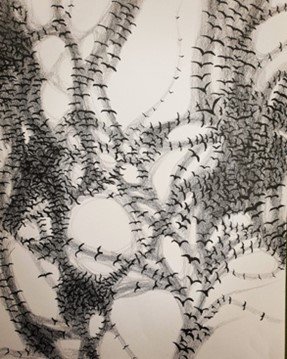

Jess Richards’ memoir Birds and Ghosts is peppered with pencil sketches of birds—peppered because the specks of bird appear like grains of pepper, coalescing into network structures. Poetry, lyric essay, memoir, prose poetry, occult reflections, and sketches join to form a map, a network, shaped like a brain by connections and synaptic firings.

In much the same way, this woven, hybrid text, out now from Linen Press, is a book about networks and relationships. It maps out the griefs of the COVID-19 pandemic as the narrator, Richards, grapples with her father’s pre-pandemic death in Scotland alongside the loss of familial and friend relationships that the closing of geopolitical borders precipitates.

The sudden relocation Richards made to New Zealand immediately after her father’s death meant that she must grieve for him from a distance, particularly as COVID-19 closes New Zealand’s borders—geopolitical and social—leaving Richards and her wife Morgan isolated from family and loved ones in a new country. This physical and social isolation brings Richards to a crisis, a reckoning: why is she so lonely, and why has she been so her whole life?

This is a text about relating; human-to-human in a time of social distance and collective fear; human-to-natural world, with all its openness and indifference; human-to-supernatural, when a father’s spirit feels impossibly far. Birds become messengers for Richards from beyond the veil; in each bird she hopes for, longs for, the ghost of her father. “A ghost,” she writes, “is a journeying bird.” As the numbers of COVID-19 dead rise, she imagines flocks of spirits rising as birds from the earth. The borders between life, the afterlife, and the spirit realm are collapsed while COVID-19 enforces distinctions, both national borders and social.

And this is a text about not relating. The lockdowns in their chosen home of New Zealand weigh heavily on Richards and her wife Morgan. Richards attempts to relate to another culture; an outsider seeking solace within a small, increasingly claustrophobic city during lockdown, her only reprieves are her writing and art, her walks with birds, and her most intimate relation with her wife.

Despite this paucity, Birds and Ghosts luminates with brilliance; Richards has an outstanding ability to tune in to her own mental state and follow her thought patterns assiduously. She notices changes in her brain like a meditating monk—and perhaps there are connections to be made between a monk and a solitary nonfiction writer. This attendance to psyche, like the autobiographical writings of St. Augustine or Michel de Montaigne, demonstrates nonfiction’s special ability to unravel inner truth—rather than to seek to mold it to narrative—and the integrity of the human desire for self-knowledge.

The role of form is key in Richards’ search. Following a plot arc would require too much to be hidden, too much to be massaged into the seams of a traditional structure. Her hybrid form has the effect, intended or not, of showing the superficiality of linear narrative when it comes to matters of the mind and psyche. By combining poetry, lyric essay, visual art, and snippets of memory we begin to see the background, the context, and the associations that linear narration might forfeit for the sake of congruency; the connections that might sprawl from a single exchange, flight, or encounter.

But the risk of solipsism is ever present in a book that goes so deeply into one’s psyche; we can only ever keep as much in perspective as our narrator can in nonfiction, when writing into the present as Richards does. I’m not sure this aspect gets resolved, and the reader must be willing to enter into that solipsistic state to experience as it were the selfhood of an other; a truly unique other, an other that imagines vividly and synesthetically, who has fantastical visions and makes completely unexpected associations.

What do you call a solipsist that is nonhuman, in the case of the birds that live in and dart between Richards’ pages; and what about that which is not living at all? What kind of ontology do ghosts—ghosts of the living, and ghosts of past selves—have?

“I’ve felt lonely my whole life and I don’t know why” becomes Richards’ ghost-like refrain. Her revelations are startling even while the emotional landscape of Birds and Ghosts in its unrelenting loneliness becomes a cage. Two thirds of my way through the book I begin to get trapped in the loneliness, like a wild bird indoors, like one of the many ghosts Richards describes as angry, moody, or trauma-stuck in various parts of the world. I hope that I’m going to be able to get out.

The ghosts enter my dreams. In my dreamhouse bathroom, a poltergeist throws me against the wall. I laugh because I want to tell the ghost they are only a story; but I fear for my safety or my life and wake starkly. My unconscious mind becomes invested in Richards finding a way out; a door to step through or a light to turn on that will banish the banshees.

The reprieve comes where Richards begins to interrogate the form of her work, seeking to prove how ghosts and birds thwart traditional human writing forms. There can be no coming and going in linear time, for example, when the self is several and the self is invisible. At this point the work becomes self-reflexive, commenting on its own shape. Ghosts, Richards informs us, are repetitions. And so we begin to see Richards’ ghosts as birds, yes, but more than that as psychological patterns, as repeating memories, mistakes, and traumas. Ghosts are part of the brain, and they mirror the brain, just as flocks of birds in the sky might mirror synapses and firing neurons.

It makes sense, then, that clinical psychology enters the text just as the reader begins to feel trauma-stuck too. Both narrator and narrative find reprieve in a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder that opens the text up to a discussion of neurodiversity.

Inner truth requires outward verification by human society, and we are grateful for the presence of Morgan, the consistent, loving wife, who appears throughout the book juxtaposed with a less sympathetic ex; through Morgan care and resilience emerge. We are grateful for the psychologist who appears over Zoom and offers the narrator perspective on her loneliness. Parents and siblings also provide sounding boards, although we do not meet the siblings or to some extent the parents in a full-bodied way, given the distance of the pandemic.

Regardless of diagnoses however, this a book by and for the lonely, for those who’ve felt misunderstood, unloved, or to be failing socially. It’s a book that holds them there in their loneliness, and then through the length of the embrace—a real embrace with a palm on the back, like Richards’ father showed her—readies them to try to move out of their loneliness, their “Lonmyth”: “the belief that no one cares / is interested, without any effort to allow people to care or show that they’re interested.”

Favorite lines of mine from Mary Oliver’s “Wild Geese,” come to me often while I read Birds and Ghosts: “Whoever you are, no matter how lonely / the world offers itself to your imagination.” Similarly, Richards’ work tells us that if we don’t have friends, if we don’t have family, and if the world is self-isolating, we have the natural world and the built world and we have our imaginations.

The amount of post-pandemic literature being published this year offers an embarrassment of riches; the pandemic gave us access to our interior lives in a way the constant buzz of contemporary life cannot. That inner life reverberates in a wholly idiosyncratic, unforgettable way throughout Birds and Ghosts. Our bird-ghost-human narrator grapples with death, lockdowns, and isolation with a needle-sharp focus that points us toward our own inner struggles; it’s up to us whether we choose to look away or choose to pay attention, and gain the benefits of looking deeply.

About the author

Melody Nixon

Melody Nixon is a Kiwi-American writer, artist, and academic. She holds an MFA in creative nonfiction from Columbia University, where she co-founded Apogee Journal in 2010. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in The London Review of Books, Literary Hub, BOMB Magazine, The Common, Conjunctions, Electric Literature, Public Books, and Landfall among others, and her essay writing has received a recommendation from The New York Times for its “sense of place.” Melody has taught creative writing at Columbia University, Massey University, and the University of California—Santa Cruz, where she currently researches poetry and race as a PhD Candidate in the History of Consciousness program.