History and Homeland in Monika Helfer’s Last House Before the Mountain

By Sarah Wingerter

The German word Heimat can be tough to translate. First and foremost, it means home as well as homeland. It connotes a particular geographic location. But Heimat also conveys more abstract concepts: a sense of belonging and identity, loyalty, comfort in the familiar, nostalgia. The term also evokes patriotism and nationalism. Austrian writer Monika Helfer’s 2020 novel Die Bagage—recently released in English under the title of Last House Before the Mountain (Bloomsbury, April 2023), and translated by Gillian Davidson—is a story of home and homeland, of belonging and alienation, of secrets that span generations. Helfer’s own literal Heimat—and the setting of this novel—is Vorarlberg, a mountainous area nestled between Switzerland, Germany, and Liechtenstein. It is a place apart: not only physically distant from the rest of Austria, but also with a dialect more similar to that spoken in nearby Switzerland and southwestern Germany than elsewhere in Austria.

Last House Before the Mountain is a modern-day meditation on an old family story. The novel depicts Maria and Josef Moosbrugger, a young couple separated when Josef is called up to fight in the first World War. Left alone to care for their four small children and their rustic homestead on the outskirts of a remote mountain village, Maria contends with poverty and starvation. But Maria is no ordinary housewife. Because she is a great beauty, she attracts—and must learn to defend herself against—her neighbors’ desire, envy, and scorn. Over the course of 175 pages, the novel’s narrator, Maria’s granddaughter, weaves in and out of past and present, juxtaposing family lore with the narrator’s own clear-eyed speculation about the events that shaped her ancestry. The narrator—a woman who has spent time in art museums in Berlin and Vienna, has had her own love affairs, and has lost her own daughter—attempts to stitch together an understanding of the events that unfolded in 1914, when Josef went off to war. She tries to map the contours of her family’s suffering and its lingering effects. Josef returns from the war a changed man; today one would recognize in his behavior the signs of post-traumatic stress disorder. Maria and the children also have changed, and for the rest of their lives, they will bear the legacy of grief and loss. Along with family resemblances and personality traits, they will pass their wounds on to the next generation. The narrator sees traces of herself in Maria. All her life, her relatives have told her she is just like her grandmother: a compliment and a warning. She possesses the same dangerous beauty; she sees history repeating itself in her own life.

Shifting between time periods and perspectives, the structure of Helfer’s novel simulates the fluid, non-linear quality of memory and imagination. The narrator allows herself to wonder: What might Maria’s life have been like if she had been born in Vienna or Berlin? What kind of future would have been possible for the precocious Lorenz, Maria’s son and the narrator’s uncle, if he had been able to move to the big city and put his keen intellect to use? In holding these questions up to the light, Helfer’s novel offers not only a glimpse into a version of history but also a reflection on the vagaries of circumstance. Against this backdrop, she explores the tensions of sexuality and desire, vulnerability and power, desperation and survival. She traces the reverberation of one woman’s trauma down through her family line.

“To bring order to memory—would that not be lying?” the narrator asks. “Lying in the sense that I would be implying that some kind of order exists.” Indeed, Helfer’s novel often blurs distinctions, rather than clarifying them. The truth is elusive, and so is identity. Helfer’s own family history inspired the novel, and Maria is based on her grandmother. Helfer has asserted, in a 2020 interview in the Wiener Zeitung, that the work is not pure autobiography. Although she had tried many times to write about her family, she said, she discovered she needed to find an intermediate form of expression. She found that form and inspiration in imagining her grandmother’s voice: “Write about me, re-invent me. Start with me.”

A best-selling author in German, Helfer has published more than a dozen novels and children’s books over her forty-year career. Die Bagage, the first of her books to be translated into English, was shortlisted for the 2020 Austrian Book Award. In 2021, Helfer won the prestigious Schubart Literature Prize. Discussing Die Bagage in a 2020 interview with Thema Vorarlberg, her region’s monthly newspaper, Helfer acknowledged that the language of her homeland is woven into her storytelling. “Surely in the tone you can hear the blackbirds singing and the fir trees rustling.” Faithful to Helfer’s spare, unadorned prose, Davidson’s translation brings those blackbirds and fir trees to English-language readers in a style steeped in fairy tale and legend, in Catholic tradition and local superstition. And given that Davidson’s translation is so true to Helfer’s text, it is all the more surprising that the novel’s English title makes such a significant departure from the original.

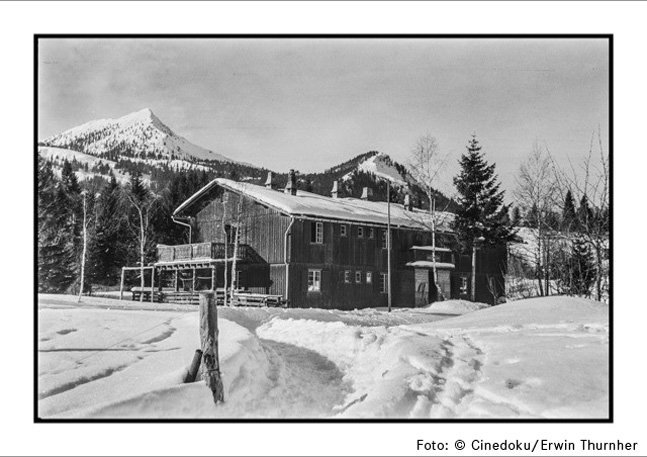

The novel’s German title, Die Bagage, refers of course to baggage, the psychic weight one accumulates and carries around over a lifetime. But Bagage is also a slang term meaning “riff-raff” or “rabble” or “undesirables.” Helfer uses this label throughout the novel to describe Maria and Josef and their children, who exist not only on the town’s geographical fringe but also on the fringe of society. Their neighbors regard them with suspicion and pity, rarely with compassion. Maria and Josef—and even their young children—seem to embrace their position as outsiders. They wear the Bagageepithet as a badge of honor, and yet they are not immune to the sting of shame their neighbors’ judgment provokes. Even the narrator claims her Bagage lineage. And Helfer, who dedicated the novel to “my Bagage,” has herself expressed a particular interest in giving voice to those at the margins. Indeed, what is perhaps most striking about this family story is its embrace of the outsider, its capacity for appreciating nuance and tolerating ambiguity, its insistence on withholding judgment. The title Last House Before the Mountain, which certainly evokes the novel’s remote setting, ignores the book’s pivotal premise. To be sure, Davidson’s translation preserves the term Bagage throughout the text, and, for added emphasis, Davidson includes a definition of Bagage as an epigraph. But because the concept of Bagage—and the identification of Maria and Josef’s family as Bagage—is so central to the novel, its absence from the title is striking. Perhaps Bloomsbury anticipated an English-speaking audience would not be interested in The Baggage or The Riff-Raff or The Undesirables. One wonders if the publisher, in choosing an English title so different from the original German, might be indicating that the audience—not just the book itself—must also be translated.

Covers of UK, US, and German editions (from left to right).

This apparent attempt to attract a particular readership might also explain Bloomsbury’s cover design choices, which could not be more different from the original. In the German edition of Helfer’s novel, the cover image is German artist Gerhard Richter’s oil painting, “Kleine Badende,” or “Small Bather.” It is a soft, blurred portrait—all earth tones and neutral shades—of a nude young woman, partially covered by a white towel and by her own crossed arms. No matter how long you look at the image, its details never quite come into focus. “Kleine Badende” embodies sensuality and vulnerability in equal measure, much like the character Maria in Helfer’s novel. Indeed, Helfer has said this painting reminds her of her grandmother, the inspiration for Maria. By contrast, the cover of the U.S. edition of Last House features Hungarian photographer Ilona Wellmann’s detailed close-up photograph of a woman: so close-up, in fact, that the woman’s face has been almost completely cropped out. She wears a high-necked, white lace garment—every thread of its delicate, web-like fabric in sharp focus—and a long gold chain with a jeweled pendant. Perhaps the frilly attire and necklace are meant to signal a work of historical fiction, but they seem overly fussy and fancy—the antithesis of theBagageimage Helfer crafts with such care in her novel. Whatever the reason for Bloomsbury’s design choices, though, readers will discover within the pages of Last House a story more weighted with ambiguity and more resonant with human complexity than its cover might suggest. They are in for a delicious surprise.

About the author

Sarah Wingerter

Sarah Wingerter is a writer and physician. She received her undergraduate degree in Comparative Literature from Princeton University and studied German literature as a Fulbright scholar at the University of Freiburg, Germany. She is an MFA candidate in Nonfiction Writing, with a secondary concentration in literary translation, at Columbia University.