Dissolution Studies by Dana Wall (Winner of the 2025 Online Fiction Contest)

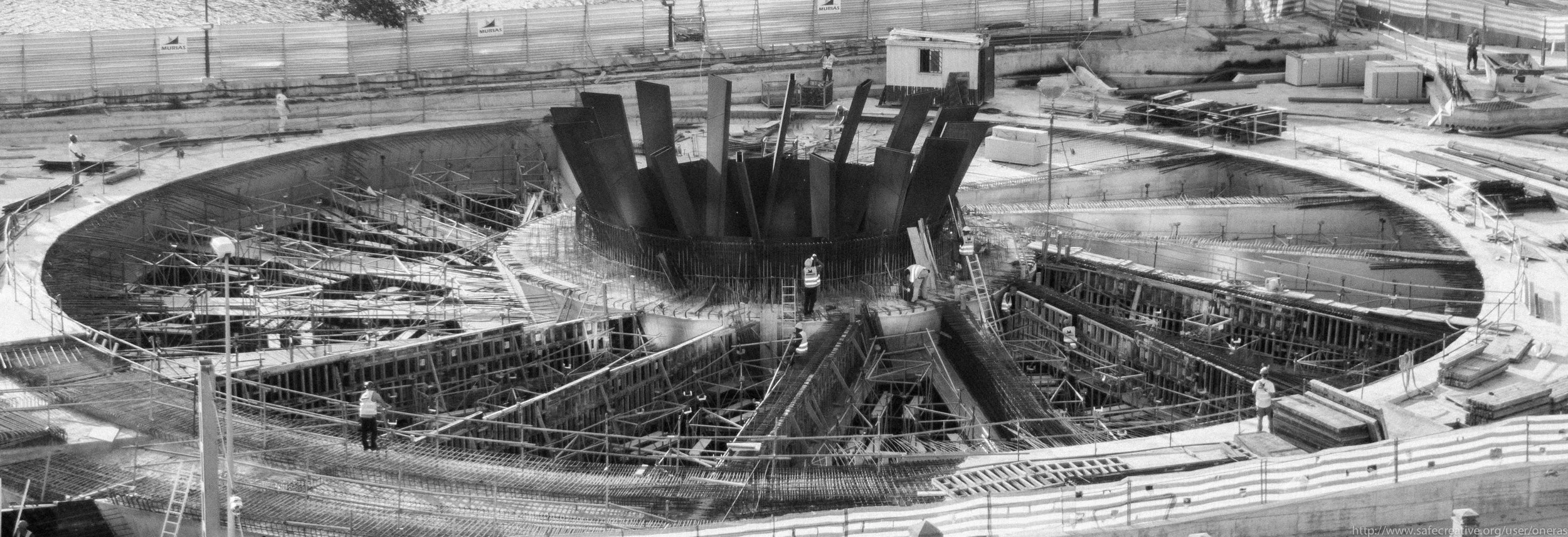

"death star engine construction" by Mario A. P. is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Dissolution Studies

When famous bodies fail, they do so at precise coordinates. Longitude: wealth. Latitude: legacy. Altitude: sixty-eight degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature at which skin preserves longest without visible condensation on glass surfaces. I've been mapping these terminal points since childhood, plotting each celestial departure on charts more detailed than any astronomer's.

The first body I cataloged belonged to Leonard Shepherd, cinematographer of eleven neo-noir masterpieces and three forgettable romantic comedies. Found supine on imported marble, temporal lobe hemorrhage, left hemisphere. The New York Times gave him six paragraphs. Variety, eleven. His ex-wife, eight words at his memorial: "He taught me to see shadows as substance."

I clipped each obituary with surgical precision, measuring column inches against net worth, correlating font size with cultural significance. My mother called it morbid. My therapist called it a coping mechanism. I call it cartography—mapping the topography of endings to understand what it means to occupy space, then not.

In Scottsdale, they die in buildings designed to frame mountain views they no longer register. In Montecito, they die beneath imported olive trees that will outlive their grandchildren's grandchildren. In Lake Como, they die with foreign soil beneath manicured fingernails. But the most fascinating deaths occur in Tokyo high-rises, those glass tombs where reputation blooms posthumously like the sakura trees they timed their deaths to coincide with.

Take Eliza Kwan, fashion empress, who selected the Aman Tokyo's Presidential Suite for her final cardiac episode. The room costs $18,000 per night, features thirty-foot ceilings, overlooks the Imperial Palace gardens, and comes with a personal butler who discovered her body arranged precisely on hand-embroidered sheets, arms crossed pharaonically over a chest that had, three decades prior, revolutionized the integration of traditional Chinese textiles into European haute couture.

What the official statement omitted: she'd stopped designing five years earlier when tremors made sketching impossible. Her most recent collection—lauded by critics who feared losing showroom access—had been entirely conceptualized by unnamed assistants from Shanghai. The pills beside her bed were not, as reported, "prescribed medication" but black market longevity supplements derived from unethical clinical trials she'd partially funded.

I knew Eliza—not well, but enough to recognize the performance art of her finale. At Milan Fashion Week 2018, she'd clutched my wrist with alarming strength after I'd asked an impertinent question about sustainability practices at her factories.

"When you've built something from nothing," she'd said, "dismantling becomes creative destruction rather than failure."

Later, reviewing the recording, I realized she hadn't answered my question. But she'd provided something more valuable: a thesis statement for her inevitable disappearance.

I wasn't surprised when the Aman's management refused to rent out the suite for three months following her death, citing "renovations." Some endings leave metaphysical residue. Some departures alter room chemistry. The Japanese have a word for this: 残留思念—residual consciousness imprinted on physical space. The finest hotels understand that grief requires quarantine as surely as any contagion.

Inside me, something collapsed the morning I read about Eliza. Not sadness exactly—we'd met only twice—but recognition of pattern, of intention. I drew a scalding bath and submerged myself until my skin bloomed red as her signature fabric dye. I wondered if death felt like this: heat without source, pressure without touch, a blurring at the edges where self meets world. I stayed under until my lungs burned like buildings marked for demolition, until the boundary between voluntary and involuntary breath dissolved.

When I surfaced, gasping, I understood what Eliza had calculated: even dissolution can be curated. Even absence can be designed.

Their bodies fail according to status—the higher the achievement, the more pristine the decline. Wealth doesn't prevent death but choreographs it, transforms biological inevitability into staged spectacle. They hire death doulas who specialize in aesthetic transitions. They select memorial photographers before selecting oncologists.

Consider Julian Mercer, Pulitzer-winning architect, who died in his most famous creation—the cantilevered glass pavilion extending over Norway's Lysefjord. Heart failure, predictable given his decades of amphetamine dependence disguised as "creative intensity." The obituaries highlighted his pioneering use of sustainable materials, his carbon-negative construction methods, his feminist approach to spatial design. They mentioned his three children from two marriages, his MacArthur "genius" grant, his guest lectureship at the Architectural Association School of Architecture.

What they excluded: the residential project in Jakarta that collapsed during monsoon season, killing seventeen construction workers whose families received settlements contingent on silence. The former students who'd contributed uncredited work to his most celebrated designs. The carbon footprint of his monthly commute between homes in four countries.

I never met Julian, but I studied him extensively for a profile commissioned and later killed by The New Yorker—too critical, my editor said, too focused on contradiction rather than genius. I'd spent three months assembling evidence of his calculated self-mythology, interviewing structural engineers who'd corrected fatal flaws in his signature cantilevers, former collaborators who'd been erased from project documentation.

After his death, I submitted a revised version to an online architecture journal. They published it alongside glamour shots of his Norwegian death chamber, my criticisms drowned in breathless praise for his "final artistic statement—dying within his greatest creation." As if his heart had stopped on schedule, as if his body had surrendered according to blueprint.

The night the piece went live, I destroyed my research materials—six notebooks, twenty-seven interview recordings, a scale model of the Jakarta disaster I'd constructed from eyewitness descriptions. I carried everything to the building's incinerator and watched pages curl and blacken, plastic melt, wood ignite. I felt something vital burning away inside me too—some belief in documentation as truth, in exposure as justice.

What remained afterward was lighter than I'd expected, almost weightless: the understanding that neither his lies nor my revelations would survive the next design trend, the next architectural movement, the next collective shift in aesthetic preference. We were both creating sandcastles at high tide, elaborate structures destined for dissolution.

Hayato Tanaka died in Tokyo three days after winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. Cerebral aneurysm, discovered by his translator who arrived for their daily work session to find him slumped over his customized Olivetti typewriter—the same machine on which he'd composed the thirteen novels, twenty-nine short stories, and five essay collections that transformed Japanese literature from post-war introspection to global cultural force.

The obituaries emphasized his artistic courage, his syntactical innovations, his unflinching examination of imperial atrocities. They quoted his acceptance speech—delivered just seventy-two hours before his death—in which he'd described literature as "the beautification of wounds too profound for ordinary language."

What they omitted: his strategic rejection of digital technologies, which created an artificial scarcity of his manuscripts. His calculated public reticence, which transformed limited interview access into currency more valuable than actual insight. His carefully cultivated aesthetic—the wire-rimmed glasses, the hand-rolled cigarettes, the monk-like daily rituals—designed specifically for posthumous mythologizing.

I interviewed Hayato once, in the small tatami room where he received select journalists. The space was performatively sparse—a single calligraphy scroll, an asymmetrical flower arrangement, cushions worn thin from decades of identical use. He poured tea with movements so practiced they seemed less human than mechanical, the physical equivalent of his famously precise prose.

"When you write about me," he said, without me having asked a question, "remember that what appears simple required the most elaborate preparation."

I understood then that I was not conducting an interview but participating in a rehearsal—one of countless identical interactions he'd orchestrated to ensure his afterimage remained consistent, controlled, curated. Even his death felt pre-written, the Nobel merely the final plot point before the narrative's perfect conclusion.

The morning I learned of his passing, I abandoned the profile I'd spent weeks crafting. Instead, I wrote a short story about a man who builds a mechanical version of himself, programs it with his complete works and speaking patterns, then vanishes into anonymous life while his automaton continues giving interviews indistinguishable from the original. I published it under a pseudonym in a literary magazine with a circulation of five hundred.

Three months later, a package arrived from Japan—no return address, only my story folded inside a first edition of Hayato's debut novel. On the title page, an inscription in precise kanji: "The student surpasses the teacher when she recognizes the performance."

I sleep with this book beneath my pillow now, not out of reverence but necessity—some nights I wake convinced I've dreamed both Hayato and myself. That we exist only as mutual fictions, characters invented to witness each other's fabricated lives.

My mother died in anonymity, her body discovered by a neighbor concerned about uncollected mail. Heart failure, unwitnessed, the timestamp estimated rather than recorded. No obituary in national publications, just three paragraphs in the local newspaper acknowledging her thirty years teaching comparative literature at Marlowe College, a small liberal arts institution nestled in the former mining town of Claverton, Maine (population 2,317). The notice mentioned her volunteer work translating medical documents for refugees and her single surviving daughter.

What the notice excluded: how she read bedtime stories in three languages, different voice for each character. How she kept every birthday card I'd ever sent in a lacquered box beside her bed. How she'd specialized in studying literary depictions of death across cultures before developing the arrhythmia that would eventually stop her heart.

I flew cross-country for the funeral, arriving too late to prevent the efficiency of modern death management—body already cremated, possessions already categorized by the estate service, apartment already deep-cleaned for showing to prospective renters. All that remained of her physical presence was a small cardboard box containing "cremains" (a word that still strikes me as obscene in its cuteness) and three plastic storage bins labeled "PERSONAL EFFECTS—FAMILY REVIEW REQUIRED."

That night, alone in her apartment—rented for forty-two years but never owned—I reconstructed her from what remained. Arranged her books by language rather than subject matter, as she'd always preferred. Placed her reading glasses on the nightstand at the precise angle I remembered from childhood visits. Brewed a pot of the oolong tea she'd favored in her final years.

I screamed then—not underwater as I had after Eliza's death, not into flame as I had after Julian's exposure, but into open air, into empty rooms, into the space her body had occupied and would never occupy again. I screamed until my voice shredded, until neighbors pounded walls, until security arrived with concerned expressions and hands hovering near concealed weapons.

"My mother," I managed to explain, pointing to the absurd box containing her reduced form. The security guard—Haitian, according to his name tag, probably with his own catalog of losses—nodded once and left without further questions. Some grief requires no translation.

Later, sorting through her papers, I found a manila folder labeled "OBITUARIES—RESEARCH." Inside: hundreds of death notices clipped from international newspapers, organized chronologically, annotated in her precise handwriting. Notes on linguistic patterns, on cultural differences in death announcements, on the erosion of information in the digital age. In the margin of one page, a question: "Why do we compress endings when they contain the most truth?"

I inherited this practice from her, I realized—not the obsession with celebrity deaths specifically, but the broader recognition that how we record endings reveals more than all our careful documentation of living. I'd misunderstood my own project completely. I wasn't mapping famous deaths; I was continuing her unfinished research.

That night, I slept on her bedroom floor, surrounded by her collected endings, breathing air still faintly scented with her presence. I dreamed of her not as she'd been in life but as text—lines of perfect handwriting unfurling across infinite pages, describing not just how people die but how they're remembered, reduced, reconstructed through language.

I maintain dual archives now—one for the famous, one for the obscure. I clip obituaries from a decreasing numbers of physical newspapers, supplement with digital records printed and preserved in acid-free sleeves. I note the discrepancies between public record and private truth, between calculated legacy and actual impact.

This isn't morbidity but methodology. Not fascination with endings but investigation of how we construct them, how we compress complex lives into column inches, how we transform messy biological cessation into narrative conclusion.

The famous still receive more elaborate documentation, of course. Their endings still occupy premium real estate in our collective attention. But in my private archive, my mother's death notice receives the same meticulous preservation as Hayato's, Eliza's, Julian's. In my cartography of conclusions, the coordinates of her passing mark equally significant terrain.

Sometimes I imagine future archaeologists discovering my collection—thousands of recorded endings spanning decades, cultures, status levels. Would they recognize it as research rather than pathology? As continuation rather than obsession? Would they understand that I was mapping not death but our relationship to it, not famous bodies but our documentation of their failures?

On my office wall hangs a single artifact from my mother's collection—the obituary of Jorge Luis Borges, whose work she taught for thirty years. She'd circled one sentence: "The mind that illuminated the labyrinthine nature of time and identity has itself become a text to be interpreted." Beside it, her annotation: "As have we all."

This is what I've come to understand through years of cataloging conclusions: we don't die as bodies only, but as texts. As narratives subject to editing, interpretation, revision. The famous simply receive more elaborate editions, more aggressive editing, more widespread distribution. But none of us escapes this final transformation from being to meaning.

When my time comes—and it will, with the same biological inevitability that claimed Eliza, Julian, Hayato, my mother—I've left instructions for no obituary at all. No public accounting of accomplishments against expectations. No carefully curated biography with strategic omissions. No transformation of a messy, contradictory existence into neat paragraphs suitable for casual consumption.

Instead, I've arranged for my complete archives to be donated to Marlowe College, with funds for a modest research fellowship in Dissolution Studies—the academic discipline I've invented to legitimize our shared obsession. Let future scholars in that quiet corner of Maine make sense of the patterns we observed. Let them continue mapping the territories of conclusion in the same halls where my mother once lectured on Rilke's conception of death.

The rest of me—the biological material, the decaying form—I've arranged to have composted under recently legalized human composting protocols. My remains will nurture a small garden of plants selected for their literary significance: asphodels from Greek underworld mythology, chrysanthemums from Japanese death poems, lily of the valley from Victorian funeral wreaths.

Even in dissolution, I'll maintain thematic consistency. Even in absence, I'll continue the research. Death isn't the conclusion of our studies but their ultimate expression—the final data point in our lifelong investigation of endings.

About The Author

Dana Wall traded balance sheets for prose sheets after keeping Hollywood's agents and lawyers in order. With a Psychology degree for character building and an MBA/CPA for plotting with precision, she earned her MFA from Goddard College. Now writing full-time, her many published flash fiction, short stories, and poetry mark milestones in her journey from numbers to words.